Digestive Enzymes for our pets

by Clare Kearney

What are digestive enzymes?

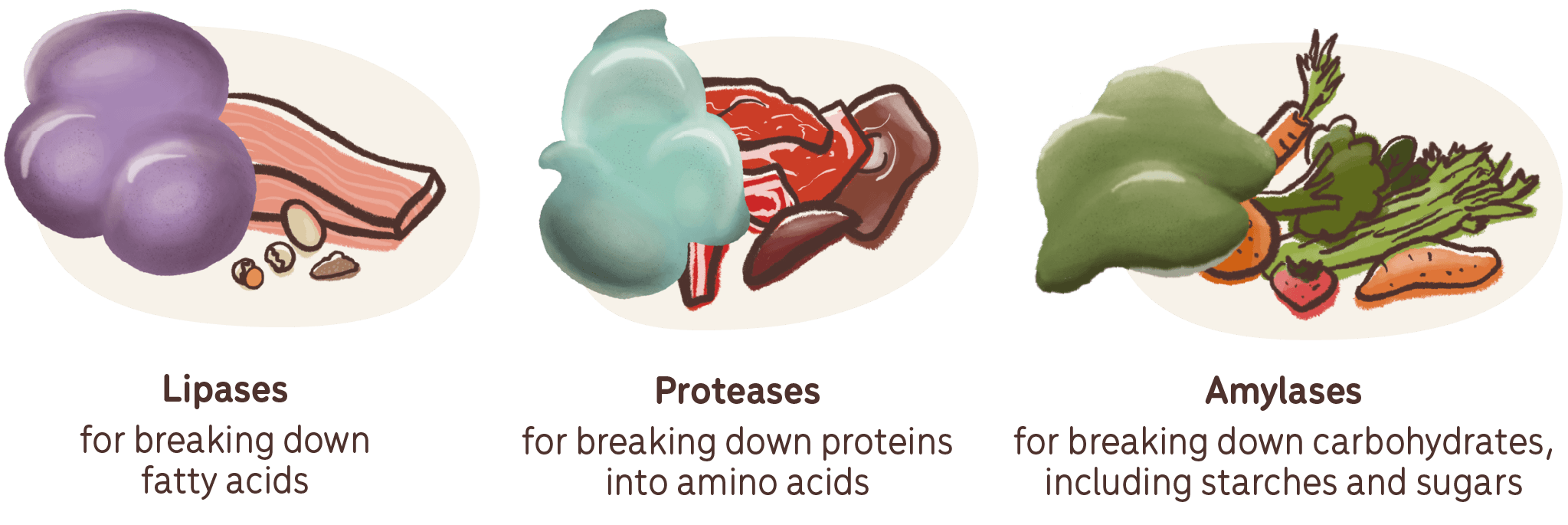

Digestive enzymes are proteins the body produces and releases in various stages of digestion, in order to break down food and absorb the nutrients it contains. They are produced largely in the pancreas, as well as the stomach, small intestine and mouth of animals, including dogs and cats. The three main types of digestive enzymes are:

Digestive enzymes are also found in foods, like fresh fruits and veggies, and we can see them in action when these foods decompose and spoil over time. This is a nifty process that facilitates the regeneration of these plants in nature, by breaking them down and spreading their seeds – also commonly seen occurring at the back of the vegetable crisper!

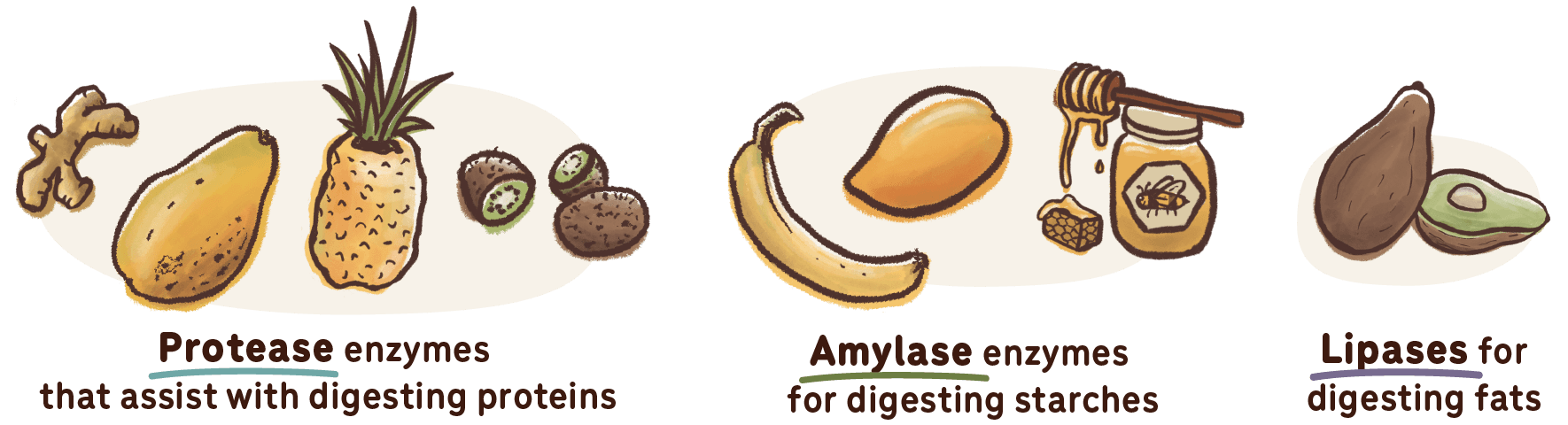

The enzymes found in certain foods – like papain in papaya and bromelain in pineapple – have been used in traditional or folk medicine for centuries, often for treating and preventing digestive disorders. These proteins are typically very sensitive to heat and processing, meaning that fresh, raw foods contain the most enzymes, with heavily processed or heat-treated foods containing very little to none.

Do cats and dogs require different digestive enzymes?

Ultimately, in healthy animals our digestion is mostly facilitated by the enzymes produced by our body. This is why it’s interesting to look at the types of enzymes each species produces or, more to the point, which ones they don’t. From this, we can deduce the foods they are metabolically designed to consume, and which ones they aren’t well suited for. In the case of dogs and cats, the key point of difference between them and truly omnivorous creatures like humans, is amylase – and specifically salivary amylase.

Most mammals that eat an omnivorous diet possess many copies of the amylase gene and large amounts of this digestive enzyme is found in their saliva, pancreas and intestines so they can digest their carbohydrate rich diets. At the other end of the spectrum, truly carnivorous animals like wolves and cats possess very few copies of this gene; wolves only have 2 copies1, compared to 20+ in humans. As a result, these animals produce little pancreatic amylase and no salivary amylase at all, strongly indicating they do not require carbohydrates in their diet, nor do they possess the ability to effectively digest them.

Dogs are more unique in that, upon splitting from wolves and becoming domesticated some 40,000 years ago, they developed additional copies of the amylase gene2. This is widely attributed to their close proximity to humans and an increase in starchy food in their diet, resulting in the need for an increase in the production of pancreatic amylase3, 4. For the most part they still do not produce any salivary amylase (or very little in rare cases5), and it’s likely their increased pancreatic amylase production has evolved out of necessity, rather than changes to their food preferences or nutritional needs.

Compare this to cats, which are thought to have been domesticated largely for the purposes of protecting food by hunting rodents, and whose food only became starch based in the last 100 years or so, and we see that their amylase production has remained largely unchanged. So, while dogs and cats can technically digest starches using the limited pancreatic amylase they produce, their digestive enzyme production seems to strongly suggest they are still better suited to a diet rich in protein and fat.

Do I need to give my pet digestive enzymes?

In a perfect world, dogs and cats would eat a species appropriate diet and absorb all of the nutrients it contains using their naturally produced digestive enzymes, supported by the enzymes found in their fresh, unprocessed food. In reality, this isn’t always the case and sometimes they need a little support.

A lack of sufficient digestive enzymes can lead to frequent digestive upset, such as gas and bloating, or even malnutrition due to the body’s inability to absorb nutrients from food. This could be periodic and brought on by stress and inflammation, or it could be genetic. If your dog is recovering from pancreatitis, your vet may recommend the addition of digestive enzymes to support their enzyme production and ensure they are obtaining sufficient nutrients from their food. And in rare cases, some animals will have a medical condition called Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency where they cannot produce their own digestive enzymes and require supplementation with each meal.

Dogs and cats eating a high starch diet may benefit from the addition of digestive enzymes to help them break down the large amounts of carbohydrates in the diet, which they are otherwise poorly equipped for. Similarly, some dogs and cats may even find that fresh fruits and vegetables can cause a bit of digestive distress or bloating. In this case adding some enzymes may help you to find a balance between obtaining the benefits of these foods without upsetting their tum – and clearing the room after dinner! Age can also deplete the body’s natural ability to produce digestive enzymes, so you may find your elderly pet is not as proficient at digesting their food and may benefit from some supplementary digestive enzymes.

If your pet is experiencing digestive symptoms, it’s important to determine if a lack of sufficient digestive enzymes is at the root of the problem. These symptoms can also be caused by things like gut dysbiosis or food intolerances, which will not be solved with digestive enzymes alone. Prolonged, unnecessary use of digestive enzymes may impact the body’s natural ability to produce them, so it’s best to use them sparingly in situations that warrant them, or when you know for certain that they’re required regularly.

Foods that contain digestive enzymes

Adding fresh foods that contain digestive enzymes is another good starting point, and you can safely introduce foods containing them for an enzymatic boost. Pineapple, papaya, ginger and kiwi fruit contain protease enzymes that assist with digesting proteins. Banana, mango and raw honey contain amylase, for digesting starches. And avocados contain lipases for digesting fats (and yes, they’re safe in moderation!). Digestive enzymes are also plentiful in fermented foods, such as lacto-fermented vegetables (eg. sauerkraut) and kefir. These foods usually contain all three main digestive enzyme groups, and you will likely find that even your lactose intolerant pet can stomach fermented dairy due to the high presence of the enzyme lactase.

If you suspect your pet is producing insufficient digestive enzymes due to an underlying medical issue, it’s always best to check with your vet before adding any supplementation. If you think they might just need a little bit of support or are struggling to digest something specific, try adding some enzyme rich foods or a digestive enzyme supplement just prior to their meal and monitor for improvements.

About the Author - Clare Kearney, Pet Nutritionist.

Clare Kearney is a pet nutritionist and writer based in Byron Bay, where she lives with her two kelpies, Tex Perkins and Pip. Clare takes a practical but science-based approach to nutrition and has a passion for fresh, whole foods for pets. She has run her consulting business HUNDE since 2015, and through it provides education about pet nutrition and the pet food industry, assisting those who wish to improve their pets’ lives through species appropriate, unprocessed foods. Clare believes that nutrition fundamentally underpins our health and that without fresh, healthy foods we can’t possibly be at our most vibrant. She sees no distinction between us and our animal companions in this respect. Her mission is to empower pet owners with information, so they can make the best possible choices for their whole family, and live long, happy and healthy lives together.